As the row of black limousines with diplomatic license plates approached the headquarters of Energoprojekt engineering and construction company in downtown Belgrade, they were greeted by employees in freshly pressed white overcoats lined up along the main entrance. The building was carefully decorated for this special occasion with rugs and flower arrangements laid out along the main lobbies. The applause reached its pinnacle as Josip Broz Tito and Kenneth Kaunda, the presidents of Yugoslavia and Zambia, approached the main entrance followed by their spouses Jovanka Broz and Beatrice Kaunda, and diplomatic delegations. It was the spring of 1970, the highpoint of Yugoslav-Zambian relations and Energoprojekt stood as the pivot of collaboration between the two socialist and post-colonial states.

(Dragan Petković, Naša najdraža i najznačanija poseta. Predsednici Tito i Kaunda posetili su našu organizaciju. Energoprojekt: Organ kolektiva inženjering organizacije Energoprojekt, Beograd, May 1970, 1-7).

(Dragan Petković, Naša najdraža i najznačanija poseta. Predsednici Tito i Kaunda posetili su našu organizaciju. Energoprojekt: Organ kolektiva inženjering organizacije Energoprojekt Beograd, May 1970, 1-7.)

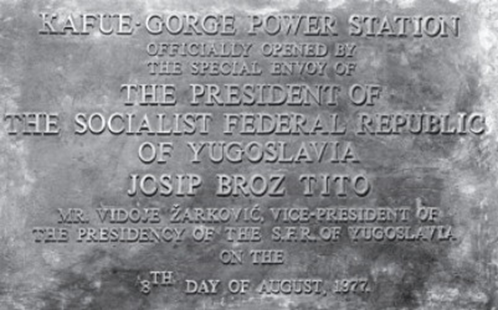

Zambia was about to host the Third Conference of the Non-Aligned Movement later that year and the Yugoslav company was given the task of building the conference hall and the surrounding facilities in Lusaka in just four months. Perhaps even more importantly, Energoprojekt was entrusted with the construction of the Kafue Gorge hydroelectric power plant, a flagship project of nationalist Zambian leadership supposed to end Lusaka’s dependency on energy imports from the neighboring, adversarial white-settler regime in South Rhodesia. At the time, some 900 Yugoslav experts and manual workers were engaged on the Kafue Gorge project together with 4,000 Zambian workers with the Energoprojekt headquarters in Belgrade overseeing this ambitious endeavor.

Energoprojekt 55 godina (Belgrade, Energoprojekt: 2006), 11.

Energoprojekt 55 godina (Belgrade, Energoprojekt: 2006), 11.

As one of the founders of the Non-Aligned Movement, formally established in Belgrade in 1961, Yugoslavia considered Zambia as the key state for the advancement of the decolonization process in Africa. After gaining independence in 1964, Zambia represented an outpost of progressive cause in southern Africa, surrounded by hostile Portuguese colonies of Mozambique and Angola to the East and West, and white-settler regimes in South Rhodesia and South Africa. The Yugoslav communists were convinced it was only a matter of time before these reactionary regimes would be swept away by the national liberation movements whose forces often found sanctuary in Zambia. Therefore, it was of the utmost importance to maintain close relationships with the government in Lusaka. Belgrade gauged that its diplomatic, military, and economic support for Zambia would expedite the liberation of other societies across southern Africa, but also pave the way for lucrative business contracts in Zambia and the neighboring states, which, it was hoped, would soon be independent under black African leadership.

For Zambia, active participation in the Non-Aligned Movement proved crucial for maintaining state stability and sovereignty in a region ravaged by Cold War armed conflict. Yet, what did Kenneth Kaunda and his cohorts seek to gain from contact with socialist Yugoslavia apart from strengthening Zambiа’s non-aligned status in international politics? The protocol of Zambian delegation’s visit to Energoprojekt in the spring of 1970 might give us some hints in this regard. After the ceremonial speeches held in the main hall, Tito and Kaunda were escorted to two additional locations in the Energoprojekt building. The first one was the computer center, whereas the second was the meeting room of the enterprise workers’ council. These sites of modernity and workers’ self-management point to the self-image that Yugoslavia wanted to project to its partners from the Global South. They can also illustrate what developing nations were searching for in exchanges with the country often seen as the pragmatic maverick of the socialist world.

Once the distinguished guests had arrived at the computer center located on the fourth floor, they were offered a showcase of the latest technological breakthroughs and Energoprojekt’s global outreach. The operators in white mantles were behind their workstations busy deciphering teleprinter tapes arriving from the company outposts and partners located in different corners of the world. They were sending greetings in Serbo-Croatian and English language which were then read aloud, “Welcome comrade Tito”, “Welcome President Kaunda”. The hosts then focused attention on the computer which tracked the progress of the Kafue Gorge project, assuring the visiting dignitaries that the construction was advancing according to plan. The company newspaper of Energoprojekt mentioned that the guests took a keen interest in the computer and commented on the rapid development of technology.

(Energoprojekt: Organ kolektiva inženjering organizacije Energoprojekt, Beograd, December 30, 1970, 9).

In its contact with the Global South, Yugoslavia was defining itself as a “somewhat more developed developing country”. This description was supposed to embody its dual nature. After the break with Moscow in the late 1940s, the Yugoslav economy was exposed to world trade and technological imports from the West, which resulted in one of the fastest industrial growths worldwide in the 1950s. Its enterprises were allegedly able to offer the latest technologies from the East and West to its developing partners without any ideological or political strings attached. On the other hand, Yugoslavia still exhibited many features of a developing country with a large rural population and the need to build the basic infrastructure. This supposedly guaranteed that bilateral economic exchange would be conducted on more equal terms, avoiding the neocolonial exploitation and dependency inherent in doing business with Western or Eastern superpowers and their allies. Zambia counted on Energoprojekt and a range of other Yugoslav companies to help build modern infrastructure at home and train the local workforce engaged on these construction sites.

Following this tangible demonstration of the host’s technological achievements in the computer room, the delegations went down to the third floor to familiarize with the unique characteristic of Yugoslav socialist modernization – the workers’ self-management. The meeting hall of the central workers’ council exhibited large panels sketching the often puzzling institutional set up of self-management in the enterprise. The central workers’ council was the highest body consisting of delegates from the councils of individual work units established in all parts the enterprise. Energoprojekt’s general director Živko Mučalov explained that the drive for decentralization of workers’ self-management was meant to give each individual worker a say in important business decisions of the company. According to Mučalov, those who create the enterprise income were also supposed to have a decisive say on how to distribute it.

Dragan Petković, Naša najdraža i najznačanija poseta. Predsednici Tito i Kaunda posetili su našu organizaciju. Energoprojekt: Organ kolektiva inženjering organizacije Energoprojekt, Beograd, May 1970, 1-7.

Unlike the Soviet bloc, where industry rigidly followed party central planning, Yugoslavia’s socialist development was conducted by workers who were theoretically at the helm of their companies. This caught the imagination of newly independent African states, where anti-colonial activists’ outrage over the exploitation of black bodies and extraction of wealth from African soil was a major battle cry. Indeed, the Zambian nationalist governemnt inherited a militant mineworkers’ union organized during the colonial regime. Ever since independence it tried to coopt the union leadership into the new government-controlled national trade union federation causing a rank and file disatisfaction which exploded around the time of Kenneth Kaunda’s visit to Belgrade in 1970.

Throughout the 1970s, the Zambian government discussed and partly implemented different legal schemes for workers’ participation in its nationalized industries. Zambian interest in the Yugslav practice of workers’ self-managment should however be differentated according to respective actors and their interests. For the government, the idea was presumably to find a way of integrating the workforce into the party-state and harmonize industral relations. On the other hand, the radical trade unionists were probably looking for an organizational solution that could provide them more independence and influence in the economy.

As the decade was coming to a close, the relationships between Yugoslavia and Zambia would become more troubled due to the falling price of copper on the world market (Zambia’s main export commodity whose sales financed most of the infastructural projects) and the rising debts faced by both countries simultaneously. The crisis of developing world brought renewed dependency on the economically most developed nations and the more conventional international business arrangements. Still, the peak of Yugo-Zambian political, economic and cultural exchanges in the early 1970s remind us of the time when self-sufficiency and direct collaboration between developing countries opened perspectives for seemingly alternative paths of development.

Goran Musić (07.11.2022)